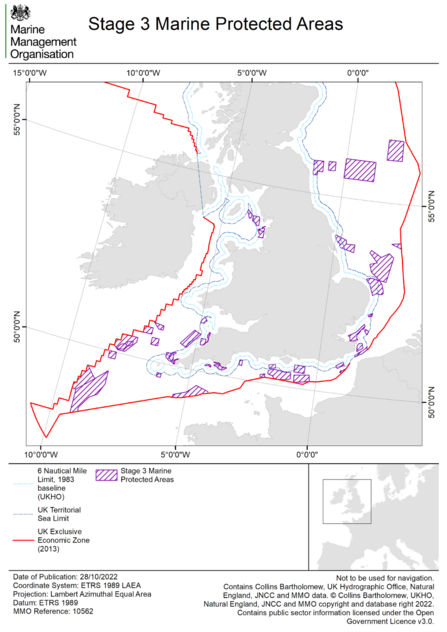

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance that you’ve seen The Wildlife Trusts’ campaign for bottom trawling to be banned in seabed Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) – you may even have signed the petition. This campaign is for the blue, but it is very much not out of the blue. We’ve been advocating for better marine protection for years, but this week’s United Nation Ocean Conference (UNOC3) presents a huge opportunity to make urgently-needed progress. Water minister Emma Hardy will be in attendance along with the environment secretary Steve Reed, and the government is already under pressure from the Environmental Audit Committee to bring about a ban on bottom trawling. Sir David Attenborough’s new hard-hitting documentary Ocean has also lit a fire in this space: for many viewers, it will be the first—and perhaps only—meaningful contact with the practice of bottom trawling.

I want to take a moment to explore what this national campaign is calling for in greater depth, and to explain how it translates to the marine conservation work we do at Cornwall Wildlife Trust. The details matter, because getting it right when we call for better marine protection is complicated. It is made all the more difficult in an information ecosystem characterised by polarisation, and simplified sound bites.